A global vertically polarized upper mantle shear speed model

(Jump to Model Downloads)

The resolving power of global seismic tomography has improved dramatically over the last several decades, due in part to the rapid growth of high-quality, broadband, 3-component seismic data. Equally important, however, has been the development of computational infrastructure, which in turn have further advanced semi and fully-automated data-processing techniques and modelling methodologies. Together, these developments have paved the way for a new generation of global tomographic models, which provide higher resolutions of lithospheric and underlying structures compared to models of only a few years ago.

To fully exploit the vast quantity of seismic data, we utilize the Automated Multimode Inversion (AMI) of surface and S-wave forms (Lebedev & Nolet, 2003; Lebedev et al., 2005; Lebedev & van der Hilst, 2008). This methodology is developed from the Partitioned Waveform Inversion (Nolet, 1990), which splits the large scale tomographic problem into more tractable inversions of each seismogram individually, similar to the techniques of Cara & Leveque (1987) and Gee & Jordan (1992). Linear equations resulting from each of these individual inversions are then combined together into one large system of equations, which can be solved using a standard least squares inversion (in this case, LSQR, Paige & Saunders, 1982). In this work, we solve for 3D perturbations in the isotropic shear and compressional speeds and 2-ψ azimuthal anisotropy, with respect to a 3D reference model.

The computational efficiency of the method enables the inclusion of much larger datasets (many hundreds of thousands of seismograms) compared to more expensive methods, which utilize only tens to hundreds of events, and several hundreds of stations. This affords a much higher degree of data redundancy, which plays a critical role in minimizing the impact of errors common to both types of methodologies, the most significant being event mis-locations and incorrect soruce mechanisms and station timing errors. Simple algorithms can then leverage the data redundancy to identify and reduce the effect of errors on the final inversion product. The increased redundancy can also enhance the validity of the approximations themselves, thanks to a much larger dataset.

Data – In this study, we have used AMI to generate an unprecedentedly large dataset of ~3/4 of a million vertical-component, multimode waveform fits. From these, a subset of more than 1.55 million most mutually consistent equations, yielded from more than half a million seismograms, were extracted to constrain a new global upper mantle shear velocity model. The more than 3500 stations from International, National, regional and temporary networks are illustrated in the station map at left, as red triangles. More than 20,000 earthquakes, between moment magnitudes of ~4.8 to 7.8 and depths spanning from shallowest crust to deep subduction zones, are indicated as yellow circles. Note the highest density of earthquakes in the seismically active western Pacific.

Map showing the >3500 stations (red triangles) and events (yellow circles) used in generating the final tomographic model.

Matrix column sums at 80 km depth, which indicate the relative sampling density. Red represents greatest sampling density, whereas green indicates the minimum sampling density. In no region is the density zero. Yellow colours represent good sampling.

Matrix column sums at 200 km depth, which indicate the relative sampling density. Red represents greatest sampling density, whereas green indicates the minimum sampling density. In no region is the density zero. Yellow colours represent good sampling.

To estimate the relative data coverage at each model knot in the model, we utilize matrix columns. As suggested by the name, for each model parameter, the matrix column is summed, which generates a relative weighting of each model parameter compared to the others. These are then plotted as maps for each depth. The two figures at left, A and B, illustrate these horizontal maps at two depths of 80 km and 260 km. In both cases, sampling is most dense beneath North America, as well as Europe and parts of easternmost Asia.

Method – AMI enables efficient, automated, accurate processing of very large numbers of vertical and horizontal component seismograms. This is accomplished through an elaborate window-selection procedure isolating signals least likely to contain scattered arrivals, combined with appropriate weighting of windows containing waves of different amplitudes and types, while enforcing strict misfit criteria. AMI assumes the JWKB and path-average approximations (Dahlen & Tromp, 1998); tie-frequency portions of each seismogram are systematically selected to contain only signals that can be accurately modelled. Additionally, in order to enhance the validity of the path-average approximation, phase velocities and their derivatives are computed as averages over approximate sensitivity areas (instead of rays), with respect to a 3D reference model.

The 3D reference model is constructed using both Crust2.0 (Bassin et al., 2000) and AK135 (Kennet et al., 1995). Above the Moho, we used a smoothed version of Crust2.0, augmented with topographic and bathymetric databases, to generate a larger suite of models encompassing greater variations in water, sediment, and crustal thickness. Several examples of these crustal models are illustrated in the figure below.

3D Reference model used in waveform inversion and tomographic model.

Left: above the Moho is a smoothed version of Crust2.0. Four example models are shown.

Right: beneath the Moho is a modified version of AK135.

The results from AMI for each seismogram are a set of linear equations with uncorrelated uncertainties, which describe a sensitivity volume average perturbation between the source and receiver. The horizontal sensitivity of each seismogram is given by the kernel: K(θ,φ). Within a cross section through the sensitivity kernel at each point along the path, the weights decrease with distance from the great-circle ray path, to a total width of ±δ, where δ is the width of the “π/2” Fresnel zone. Vertically, the S-velocity perturbations are parameterized on 18 “stem” nodes: 7, 20, 36, 56, 80, 110, 150, 200, 260, 330, 410-, 410+, 485, 585, 660-, 660+, 809, and 1007km, whereas P-

Top: Red circles are model grid. Yellow circles show an example Fresnel zone on the fine integration grid. The size of the circle represents the grid node weight. Blue circles represent the weight of each model knot, interpolated from the integration grid nodes.

Bottom: Vertical basis functions used in the tomographic inversion.

velocity uses only 10 parameters: 7, 20, 36, 60, 90, 150, 240, 350, 485, and 585km. The stem nodes are the vertices of triangular basis functions, with the 410 and 660 km discontinuities represented by half triangles.

The inversion solves directly for perturbations in P, S, and 2-ψ S-velocity azimuthal anisotropy with respect to our 3D reference model. As verified by Lebedev & van der Hilst (2008), perturbations in P-velocity can not be resolved independently using Rayleigh-wave data. To avoid these trade-offs the difference between isotropic P and S velocity perturbations are damped; this offers greater freedom to the inversion, as opposed to forcing a rigid coupling. Regularization during inversion is carried out in the form of lateral and vertical smoothing and slight norm damping, to stabilize the mixed-determined inversion. The smoothing is the primary control, whereas damping plays a secondary role. In this work, we examine the isotropic shear speed portion of the model, and leave the anisotropic component for further work.

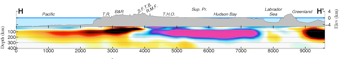

Results – Our new isotropic global upper mantle and transition zone Sv velocity model, SL2013sv, is computed on a ~280 km triangular grid using 521,705 vertical component broadband seismograms. The final model has a variance reduction of 90%. In the horizontal slices plotted at right, perturbations are with respect to the mantle reference, indicated below the depth. In the vertical cross sections, perturbations are in m/s; at shallowest depths above the Moho, perturbations are instead with respect to our modified Crust2.0.

Map of lateral variation in seismic shear velocity (Sv) at 56km depth. Warm colours (reds) denote slower wave speeds, indicative of warmer temperatures and possibly the presence of melt. Cool colours (blues), representing fast speeds, are commonly associated with ancient and stable lithosphere beneath continental cratonic regions, or fast lithosphere within subduction zones. We can clearly see a number of low velocity regions around the globe, including strong negative anomalies at mid ocean ridges, as well as continental low velocity zones, including western North America, and the partially molten Tibetan lower crust.

Map of lateral variation in seismic shear velocity (Sv) at 150km depth. Warm colours (reds) denote slower wave speeds, indicative of warmer temperatures and possibly the presence of melt. Cool colours (blues), representing fast speeds, are commonly associated with ancient and stable lithosphere beneath continental cratonic regions, or fast lithosphere within subduction zones. The dominant features are the high velocity lithospheres of the major cratons around the globe.

The long wavelength upper-mantle features in our new model are in agreement with observations from past models. Where we observe the most improvements are in the fine-scale regional regional structures. The prominent features in our model provide a direct expression of the tectonic processes. We observe sharp velocity contrasts across many tectonic boundaries, for example, subduction systems and associated back-arc volcanics, actively deforming regions, and continental orogens. The strongest velocity anomalies are associated with stable continental cratonic platforms (positive), mid-ocean ridges and rift systems (negative), and back arcs (negative).

In oceanic regions, we have captured striking images of spreading ridge anomalies which are more localized near the ridge axis in the uppermost mantle than in past models. In continental regions, we conclude that the high-velocity, cold cratonic roots are not required to extend far beyond 200 km depth. Between 150km and the base of the transition zone, we obtain clear images of most of the major subduction zones.

Observed agreement of the deep crustal and upper-mantle structure resolved by the model with regional-scale surface tectonics and the clear recovery of transition zone structures show that the significantly increased data coverage and data redundancy translate into significantly improved resolution provided by the new generation of tomographic models of the lithosphere and upper mantle

The main features of the model are clearly evident in the animation (below) which begins at 20km depth and continues to 300 km depth, at 5km intervals. The colour scale is fixed at a saturation of 8%, as indicated beneath. The spreading ridges come into focus, then have dissipated by 150km. Additionally, the different high velocity cratons around the globe can be seen persisting to depths of 200km, though with almost no strong signature beneath 250km depth, in most cases.

Animation through SL2013sv in the upper mantle, from 20 to 300 km depth. Perturbations saturation at plus/minus 8% from the reference at each depth.

Model Download

We have provided two different versions of the model to download, which are on two different horizontal grids. The first archive, SL2013sv_tri-grd, contains a file expressing the model perturbations on the original ~280km triangular grid used in the inversion. The second archive, SL2013sv_0.5d-grd, contains the model re-gridded to a constant resolution of 0.5 degrees laterally. Each archive contains a README file identifying the model file and its format.

*** NOTE ***

Below are several versions of the model. The most recent version, v2, begins at a depth of 20km; this is in the depth range of our 3D crustal reference model. As explained in the README file, several options are provided for plotting: perturbations with respect to our (3D) reference model, Absolute Velocity, or perturbations with respect to the mean velocity at a given depth. Feel free to contact the authors if you are unclear of the differences. The older version, v0.5m, does not contain the 3D crustal model, and begins at a depth of 50 km.

****************

If using the model, please reference:

Schaeffer, A. J. and S. Lebedev, Global shear-speed structure of the upper mantle and transition zone. Geophys. J. Int., 194 (1), 417-449, 2013. doi:10.1093/gji/ggt095 [Link]

Version 2.1a: Absolute 1D Profiles (April 2018):

- SL2013sv_0.5d_1DAbs_v2.1a.tgz – Added archive of complete 1D profiles extracted for the SL2013sv model at 0.5 degrees laterally across the globe. These 1D profiles include the discontinuity structure of the reference model. Complete Vp/Vs/Density profiles are present, however we highlight that the inversion itself was focused on the accurate recovery of Vs and not the other properties.

Version 2.1 (August 2016):

- SL2013sv_tri-grd_v2.1.tar.bz2 – README updated with new contact information.

- SL2013sv_0.5d-grd_v2.1.tar.bz2 -README updated with new contact information.

Version 2 (July 2014):

- SL2013sv_tri-grd_v2.tar.bz2 – Triangular model shell knots (7, 842 shell knots at each depth).

- SL2013sv_0.5d-grd_v2.tar.bz2 – Gridded 0.5 degree lateral resolution spanning (-180,180) longitude and (-90, 90) latitude.

Version 0.5m (April 2013):

- SL2013sv_tri-grd_v0.5m.tar.bz2 – Triangular model shell knots (7, 842 shell knots at each depth).

- SL2013sv_0.5d-grd_v0.5m.tar.bz2 – Gridded 0.5 degree lateral resolution spanning (-180,180) longitude and (-90, 90) latitude.

Thanks for such a contribution. I am new PhD student in Indian Institute of sciencne, Bangalore, in India. I am planning to work in the field of Seismology and Geodynamics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for keep your model updated, improved and accessible.

LikeLike